On November 2, Ajax and I headed for Tiger Mountain, a half-hour drive from home. The upper trails had been closed for private logging since July. I was eager to learn whether I’d still have a good place to hike during the approaching winter months. This blog post is a photographic tribute to Tiger Mountain’s beauty, despite the devastation on all three summits due to logging.

A Trip Up Tiger Mountain Trail

The forecast called for cloudy, dry weather before noon. We left the parking lot at 8:15, unsure what we’d find or where we’d go. A perfect day for a coddiwomple.

A man without a pack headed down the trail just ahead of us. When he turned toward the Section trail, I decided we’d try our usual route but in reverse. We turned left onto Tiger Mountain Trail. Doing so would give me an opportunity to make sure the calf I’d strained on our Pratt Lake trip two weeks earlier would be okay. (It was!)

Evergreen versus Deciduous

Right away I noticed the difference in our surroundings compared to five months ago. Deciduous leaves blanketed the trail in yellows and browns while the ferns remained lush and healthy. Yellow carpeting provided the illusion of a sunnier day both from the brightness in the sky and the path under my feet. Unless you know the trail, it might be tricky finding the path through so many fallen leaves. But over the past eighteen months, Ajax and I have hiked many of Tiger’s routes. While I don’t quite know it like the back of my hand, it’s becoming familiar.

We took a brief break (clothing for me, water for Ajax) just before nine and didn’t see a single person, one of the reasons I enjoy going mid-week, early morning, in the off-season, on a less-used trail, and in transitional weather. It felt like we had the mountain all to ourselves.

Disturbance of the Peace

A few minutes later, the first buzzing of chain saws pierced the air. My heart sank. Loggers were already at work. We would probably hear them for the rest of our hike.

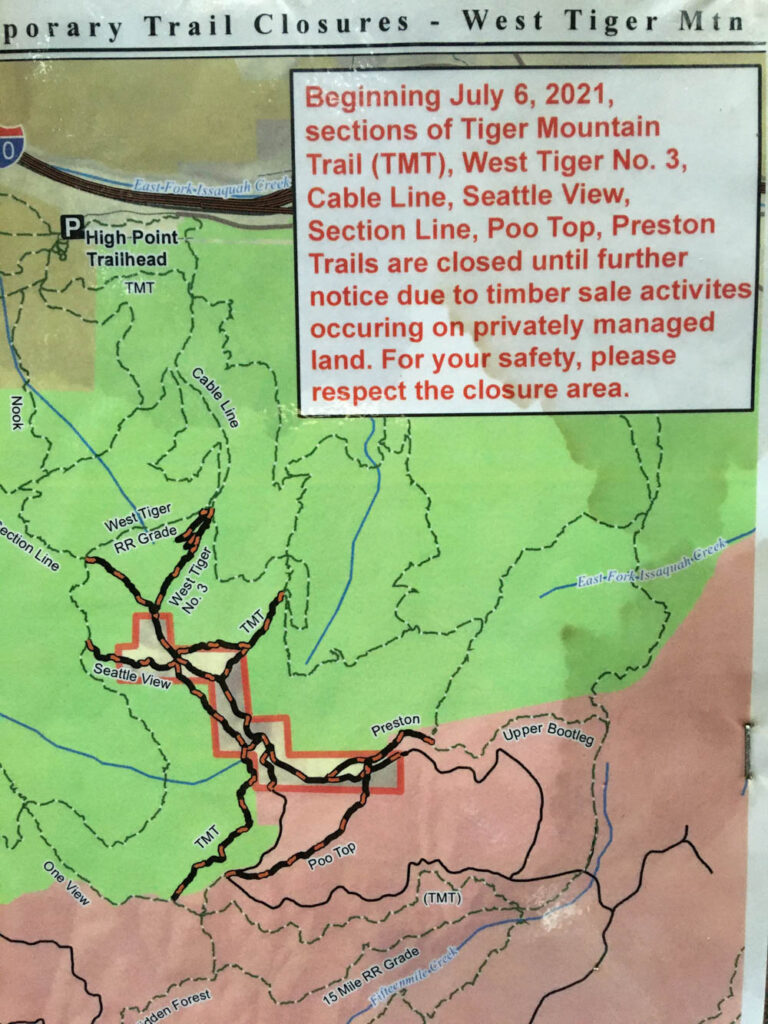

I knew from recent posts on Washington Trails Association that several routes to the summit had been closed. Tiger Mountain (Exit 20 off I-90 east of Seattle) is at low elevation and perfect for hiking year-round. I wanted to see for myself what side trails remained open for future winter outings.

I have many fond memories of snow blanketing the road between Tiger 2 and Tiger 1. Ajax and I have taken many jaunts through the forest, boughs laden with heavy snow.

Our Upward Coddiwomple Continues

Unfortunately, shots like the snowy one on this blog are only memories. As you can see from the map above, the top-most portion of Tiger Mountain has been logged. The good news is, tons of wonderful hiking remains, as long as you’re not summit-hungry. Tiger Mountain Trail and the Railroad Grade both provide ample low elevation hiking, only a portion of which is currently off-limits.

We followed the TMT until we reached the marker for “K3 / Unmaintained” and followed it steeply up and across several running streams. Section/Nook, TMT, Talus Rocks, and RRG trails all have running water on them; Cable and W. Tiger 3 do not.

We leapfrogged upward until we reached the sign indicating the summit of West Tiger 2, a half-mile away, cordoned off with obnoxious orange netting. After turning east we continued beneath Tiger 1’s summit until the sounds of logging drowned out the sounds of wildlife and running water.

At our designated turn-around time, we headed back the way we’d come, navigating around a large downed tree across upper K3. When we reached the Cable Line Trail, I decided I really wanted to see what was left of the summit. We headed straight up.

A Mountain Being Loved to Death

The erosion on the Cable Line trail stunned me. Cables hang in places, looking almost like hand lines. Usually, a foot (or more) of soil covers them. So many hikers have traveled this trail, it looks as bad as the old route on Mailbox. Maybe worse.

At the sign indicating .6 miles to the summit, we turned off the deeply rutted track and continued on the much nicer main trail to the summit of West Tiger 3. Or, I should say, what remains.

Ugly Summits

Large orange barriers and warning signs indicate that the area is being actively logged and to keep out, courtesy of Weyerhaeuser. The summit of West Tiger 3 has been completely destroyed.

Logging has moved east; the summits of Tiger 1 and 2 are still being decimated. Ugly, gaping wounds stretch in every direction. My heart goes out to the gray jays, chipmunks, woodpeckers, songbirds, and other critters who once called the summits home.

And to all those hikers in the Puget Sound region who no longer have access to a great training route. Yeah, sure, now you can see Mt. Rainier from all three summits, but with no foreground.

To a hiker gawking at the destruction, I commented, “This may be worse than a volcanic eruption.” At least volcanic material becomes fertile ground, given enough time.

More Questions than Answers

So many questions popped into my mind. Does Weyerhaeuser plan to plant more trees? What happened to the Hiker’s Hut on Tiger 1 at 2800 feet elevation?

Could I use this as a backdrop for a middle-grade novel? How long before the loop from 3 to 2 to 1 becomes beautiful again? Did the geocache my daughter once found between Tiger 3 and 2 get destroyed by loggers?

What happened to the memorial spot on a little turn-out just east of Tiger 3? Tiger is so much more than trees. It holds treasured memories. Life stories.

I certainly understand that as the human population continues to explode, resources become more and more precious. And I get that privately owned recreational lands can be used as the owners wish. This is the first time I’ve experienced land previously used for public recreation becoming an ugly harvestable commodity.

It stings.

Tiger Mountain’s Beauty on Our Return to the Car

On our hour-long hike down the Section Trail, we only encountered one other gentleman on his way to the summit. The sound of logging dimmed and disappeared behind me, almost like a bad dream. Around us we could once again hear birds calling, squirrels chittering, and water running. My sadness turned to peace as I relished the beauty that remains intact on the rest of Tiger Mountain. The mushrooms and fungus keep doing their job decaying old logs.

Moss continues to drape branches and birds continue to create peepholes. I still recognize favorite trees from earlier photographs. No vibrant reds or oranges to speak of, but the textures and nuances of the greens, yellows, and browns soothed me.

And when we reached the large stump where I take selfies, Tuesday was no exception. What goes through our pets’ heads when they see something change so dramatically? Did the unfamiliar noises disturb him? Or was he merely hungry? What caused the startled expression on his face?

Tiger Mountain’s Beauty Endures: Take-aways

As I reflect on our November second hike, I ponder the take-away messages Mother Nature left with me:

- Look for the good, the beautiful, the positive in any change, whether we perceive it as good or bad. It’s there. Logging is ugly. Yet Mother Nature heals, and with time there will again be beautiful forest growth on Tiger 1, 2 and 3. Meanwhile, the bulk of Tiger Mountain remains unaffected. It’s truly a beautiful place.

- Express gratitude for what is. I am so grateful for my photo log of hikes when Tiger’s summits were pristine. I can look back on our many, many trips and remember, fondly, all the beauty we discovered as a family, with friends, or solo with my pup.

- Understand the difference between change we can control (like what job to take, how much to eat, or where to move) and change we can’t (such as natural disasters, COVID or social justice policies, and local logging).

- Choose to do something to manage the impact of those changes we can’t control. We have a voice; use it.

- Find truth and comfort in “Serenity, courage, and wisdom.” And trust that Mother Nature will prevail.